Fistula

Millions of women need psychological and medical care for obstetric fistula after complicated childbirth.

An obstetric fistula is a hole between the vagina and the bladder or rectum through which urine or stool leaks continuously.

They are devastating injuries resulting from complicated childbirths and affecting more than two million women worldwide.

While any woman can be susceptible to fistulas, most cases occur in African countries.

It's a mostly hidden problem affecting young women who give birth at home in poor, remote areas with very limited or no access to maternal healthcare.

If a woman survives a complicated birth and suffers a fistula as a result, she may be shunned by her family and community.

Because of this social exclusion, it is even less likely the sufferer will receive care.

Our healthcare teams work with pregnant women to prevent the occurrence of obstetric fistulas, while at the same time, treating those with the condition and providing psychological support to fistula sufferers to help them rebuild their lives.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

Fistula: Key facts

2 million

WOMEN LIVING WITH FISTULA WORLDWIDE

50-100,000

NEW CASES OF FISTULA EACH YEAR

337,000

BIRTHS ASSISTED BY MSF IN 2023

Almost all fistulas are caused by obstructed labour. In remote African regions, where there are few hospitals or midwives and obstetric care is scarce, complicated childbirth can result in a woman being in labour for days.

Without access to emergency Caesarean sections, these complications can be fatal. If the woman survives the labour, permanent injuries to the birth canal often result.

During childbirth, the delivery of a baby may stop because the head of the child is too big, or the pelvis of the mother is too small. A delivery may also stop because the uterus is not contracting properly.

As the baby’s head presses against one part of the birth canal, the surrounding tissue eventually dies and creates a hole, or a fistula – an abnormal connection between the vagina and the bladder, the vagina and rectum, or both.

This hole will never heal naturally and, more often than not, the baby will be stillborn, adding yet more suffering for the mother.

While very rare, our surgeons have also witnessed a small number of fistula cases resulting from extreme sexual violence.

Because of the abnormal opening to the bladder or rectum, a woman suffering from a fistula will constantly leak urine or faeces through her vagina. The leaked fluids cause an unpleasant smell and can cause ulcers or ‘burns’ on the woman’s legs.

Women often reduce their fluid intake drastically to try and reduce the flow of urine, which can result in kidney disease and bladder stones.

In most cases, women with fistulas develop psychological symptoms. Because of the physical symptoms, they are often ostracised by their community and abandoned by their husbands, who will take another “healthy” wife.

Due to the birthing complications, women in some cases suffer nerve damage as well, causing paralysis in one or both of the woman’s legs, or leaving her with difficulties in flexing her feet – a condition called drop foot.

These problems can further isolate a woman, which, in turn, can lead to malnutrition due to her exclusion from society.

With good obstetric care, fistulas are preventable. In developed countries, fistulas have all but disappeared.

In some cases, a simple repair may take only 45 minutes to complete, but many cases are more complex and require several operations by highly skilled surgeons. Only a few institutions in Africa teach these specialised surgical skills.

After the operation, the patient will need a bladder catheter for a couple of weeks and will be taught pelvic floor exercises to strengthen her muscles.

Thankfully, women who have had a fistula repaired are able to have a healthy child in the future, if they receive appropriate antenatal care.

Training local midwives to help mothers give birth safely is vital. They can spot whether a mother is having difficulty giving birth and can arrange help before it is too late.

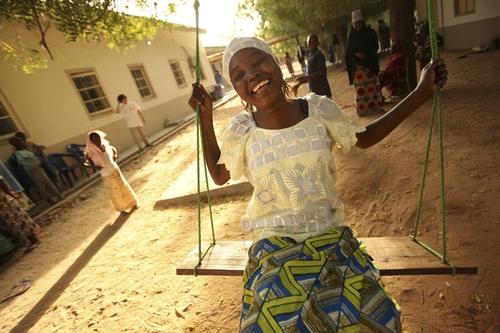

Total treatment, however, goes beyond the surgical aspect. Because of the stigma attached to fistulas, MSF teams also provide psychological and psychosocial aftercare to help reintroduce fistula sufferers back into their communities.

Since 2008, MSF's specialist hospital in Jahun, northern Nigeria, has admitted and cared for more than 5,700 patients with fistula.

Today, our teams also treat obstetric fistulas in two other centres in Burundi, Chad.

Fistula: News and stories