Tanzania: "I'm so happy my daughter can be cured of malaria"

While rates of malaria are reducing globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 212 million new cases emerged in 2015.

An estimated 429,000 people died: around 70 percent were children under five.

In recent months, refugees in northwest Tanzania have been suffering an increase in the mosquito-borne disease.

Tanzania is now home to over 310,200 Congolese and Burundian refugees, hosted across three camps - Nyarugusu, Nduta and Mtendeli.

The country's ongoing rainy season provides perfect conditions for mosquitoes. Meanwhile, overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in communal mass shelters allow the illness to spread rapidly.

Between January and March this year, MSF treated 55,400 malaria patients in Nyaragusu and Nduta.

We currently run two malaria clinics within Nyarugusu camp, where our teams test, diagnose and treat refugees.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

Photostory: Pascal and Billy

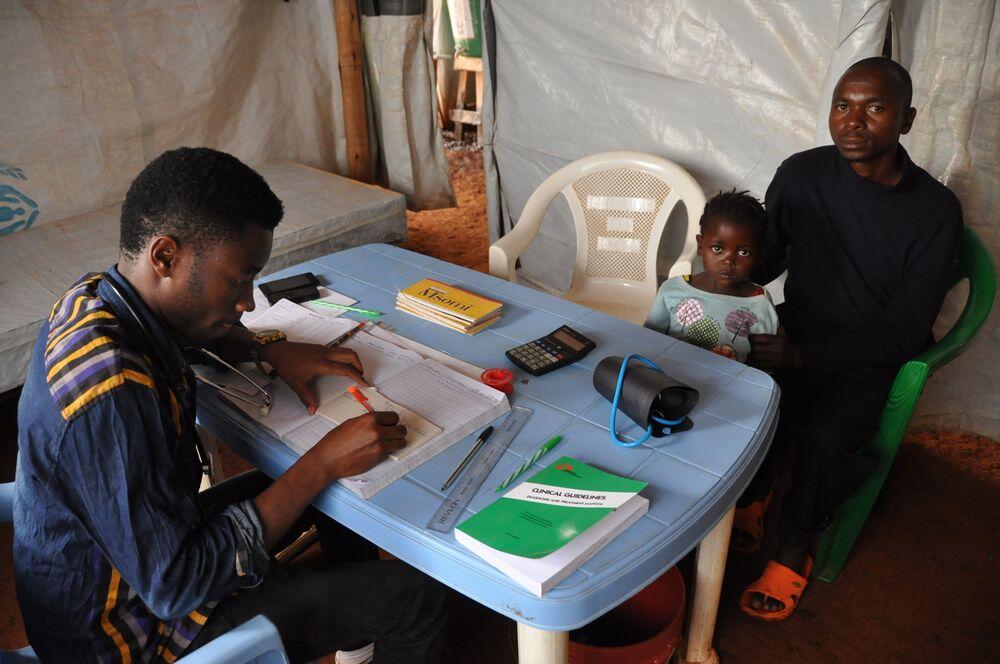

Pascal Nzambimana, 34, and his daughter Billy, aged three, wait for a medical consultation at an MSF health post at Nyarugusu refugee camp.

The father brought his child here when she developed a fever and started vomiting.

Billy's symptoms are typical of malaria: fever, headache, joint pains, vomiting and other flu-like symptoms.

Saidi Lukozi, MSF nurse assistant at Nyarugusu camp, tests her for the disease. The young girl receives a small pin-prick to her finger to extract a drop of blood. This is tested immediately on-site, to see if malaria parasites are present.

This is the most reliable way of diagnosing malaria in the camp: little training is needed in order to administer the tests; no additional laboratory equipment is required; and the results are fast and simple to interpret.

Soon Billy and her father are called into a separate room in the health post to receive their test results. Deogratious Rupdena, MSF clinical officer, breaks the news. As suspected, Billy has malaria.

He checks Billy's vital stats, performs a complete physical examination and then prescribes her with anti-malarials.

Fortunately, her malaria isn`t severe, so she will not need to be transferred to the camp hospital.

In 2016, MSF treated 46,380 refugees in Nyarugusu for malaria. Children under the age of five, like Billy, accounted for 23 percent of all positive diagnoses.

Globally, infants and young children are the group most vulnerable to malaria. This is because they do not have fully developed immune systems to defend against the disease.

After her consultation, Billy is given her anti-malarial tablets and some water to help her swallow the first dose. An MSF nurse aide explains to Pascal how and when Billy must take the medicine once she is back at home.

We use artemisinin-based combination therapy, the world's most effective malaria treatment - recommended by the WHO since 2001.

Alongside treatment, we conduct health promotion sessions to teach people how they can prevent malaria, to recognise symptoms, and how and when to seek treatment.

In 2016, MSF conducted 82,360 health promotion sessions in Nyarugusu camp, almost 50 percent of which were for malaria. We also distributed 65,000 mosquito nets to help prevent the disease.

In 2017, we sprayed larvicide in high-risk zones to prevent the breeding of mosquitoes.

“I'm so happy that my daughter can be cured," says Pascal, ready to take Billy home. "Now I understand more about the illness, I hope I'll be able to prevent the rest of my family from getting sick in the future.”

Anti-malarials in hand, Billy and Pascal leave the clinic.

But with 7,010 cases of the disease seen by MSF in March alone, our work to prevent, detect and treat malaria in Nyarugusu continues.