Sudan: Country facing colossal man-made catastrophe after one year of war

In Sudan, one year after the start of the war between the Government-led Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the country is facing a colossal man-made catastrophe. It has become one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises for decades.

Urgently enabling safe humanitarian access is a matter of life or death for millions of people in Sudan.

As an international conference of governments and officials, aid organisations and donors meet in Paris on 15 April to discuss ways to improve the delivery of humanitarian aid, Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) is making an urgent call for them to immediately scale up the humanitarian response.

Millions of people are at risk, yet the world is turning a blind eye as the warring parties intentionally block humanitarian access and the delivery of aid.

“Every day we see patients dying because of violence-related injuries, children perishing due to malnutrition and the lack of vaccines, women with complications after unsafe deliveries… Despite all this, there is an extremely disturbing humanitarian void”

The United Nations (UN) and member states must redouble their efforts towards negotiating safe and unhindered access, increase the humanitarian response and prevent this already desperate situation from deteriorating any further.

“People in Sudan are suffering immensely as heavy fighting persists —including bombardments, shelling and ground operations in residential urban areas and in villages,” says Jean Stowell, Head of MSF Sudan.

“The health system and basic services have largely collapsed or been damaged by the warring parties.

“Only 20 to 30 percent of health facilities remain functional in Sudan, meaning that there is extremely limited availability of healthcare for people across the country.”

Traumatic injuries and mass displacement

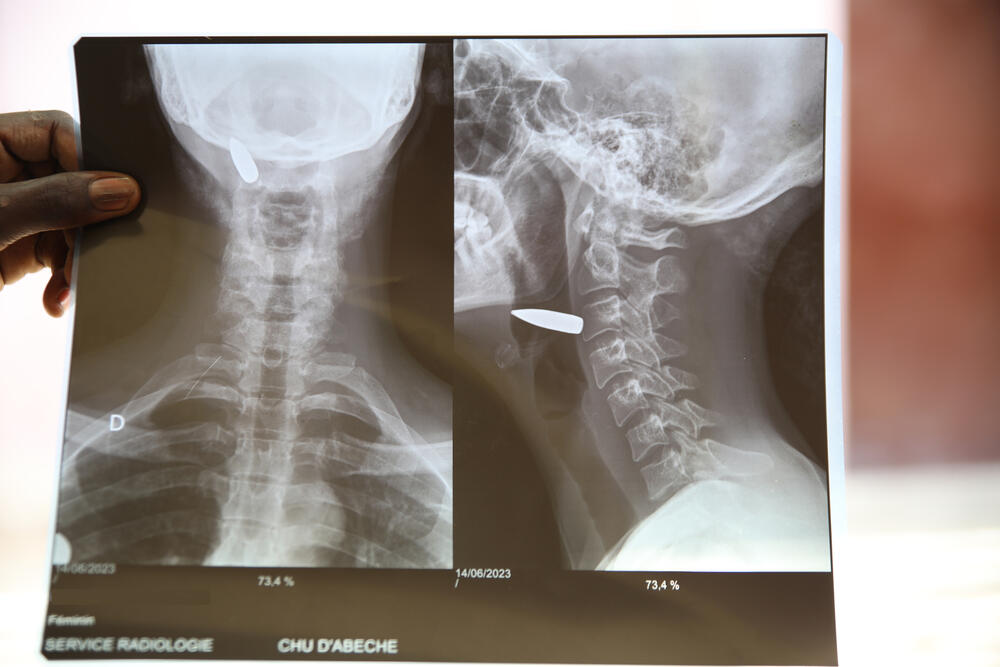

In areas close to hostilities, MSF teams have treated women, men and children directly injured in the fighting, including those with shrapnel, blast and gunshot wounds, and injuries from stray bullets.

Since April 2023, MSF-supported facilities have received more than 22,800 cases of traumatic injuries and performed more than 4,600 surgical interventions, many of them related to the violence which occurred in Khartoum and Darfur.

In Wad Madani, a town surrounded by three active frontlines, we currently see 200 patients per month with violence-related injuries.

According to the UN, more than eight million people have already been forced to flee their homes and have been displaced multiple times, while 25 million – half of the country’s population – are estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance.

“Every day we see patients dying because of violence-related injuries, children perishing due to malnutrition and the lack of vaccines, women with complications after unsafe deliveries, patients who have experienced sexual violence, and people with chronic diseases who cannot access their medicines,” says Stowell.

“Despite all this, there is an extremely disturbing humanitarian void.”

Help us prepare for the next emergency

Obstructions to aid

Although MSF works in good cooperation with the Ministry of Health (MoH), the Government of Sudan has persistently and deliberately obstructed access to humanitarian aid, especially to areas outside of its control.

It has systematically denied travel permits for humanitarian staff and supplies to cross the frontlines, restricted the use of border crossings, and established a highly restrictive process for obtaining humanitarian visas.

22800

Traumatic injuries treated by MSF since April 2023

30,000

Children with acute malnutrition treated by MSF since April 2023

8400

Births assisted by MSF since April 2023

“Today, our biggest challenge is the scarcity of medical supplies,” says Ibrahim*, an MSF doctor working in the capital Khartoum.

“We've run out of surgical equipment, and we are on the brink of stopping all work unless supplies arrive.”

Khartoum has been under a blockade for the past six months, while a similar situation has been impacting the city of Wad Madani since January.

In RSF-controlled areas, where many different militias and armed groups also operate, health facilities and warehouses were frequently looted in the first months of the conflict.

Incidents such as carjackings continue on a regular basis and medical workers, particularly from the Ministry of Health, have been harassed and arrested.

In hard-to-reach areas like Darfur, Khartoum or Al Jazirah, MSF often finds itself the sole or one of the few international humanitarian organisations present, while needs far exceed our capacity to respond.

Even in more accessible areas such as White Nile, Blue Nile, Kassala and Gedaref states, the overall response is negligible: a drop in the ocean.

One example is the catastrophic malnutrition crisis in Zamzam camp in North Darfur, where there have been no food distributions from the World Food Programme since May 2023.

Almost a quarter of the children we screened there in a rapid assessment in January were found to be suffering from acute malnutrition – seven percent were severe cases.

At the same time, 40 percent of pregnant and breastfeeding women were suffering from malnutrition, and there was a devastating mortality rate across the camp of 2.5 deaths per 10,000 people per day.

“The situation in Sudan was already very fragile before the war and it has now become catastrophic,” says Ozan Agbas, MSF Emergency Operations Manager for Sudan.

“In many of the areas where MSF has started emergency activities, we have not seen the return of the international humanitarian organisations that initially evacuated in April.

Khadija Mohammad Abakkar, who had to flee her home in Zalingei, Central Darfur, in search of safety, recounts how difficult it was to survive without humanitarian assistance:

“During the fighting, there was no access to healthcare or food in the camp. I sold my belongings to earn some money for food.”

Urgent action

While these are difficult conditions in which to operate, the response should have increased, not diminished, especially in the areas where access is possible. Increased efforts are urgently needed by all humanitarian actors and organisations to find solutions to these problems and scale up activities across the country.

“The United Nations and their partners have persisted in self-imposed restrictions on accessing these regions and, as a result, they have not even pre-positioned themselves to intervene or establish teams on the ground when opportunities arise,” says Agbas.

MSF calls on warring parties to adhere to International Humanitarian Law and the humanitarian resolutions of the Jeddah declaration by putting in place mechanisms to protect civilians and to ensure safe humanitarian access to all areas of Sudan without exception. This includes stopping blockages.

MSF also calls on the UN to show more boldness in the face of this enormous crisis – to focus on clear results related to increasing access so that they actively contribute towards enabling a rapid and massive scale-up of humanitarian assistance.

MSF also urges donors to increase funding for the humanitarian response in Sudan.

*Name changed to protect identity

MSF and the crisis in Sudan

On Saturday 15 April, intense fighting broke out across Sudan with a wave of gunfire, shelling and airstrikes.

The violence between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has trapped millions of people in the middle of an unexpected conflict. Many have been forced to flee their homes while access to essential services such as healthcare has become increasingly difficult.

Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams already working in Sudan have been responding to the crisis since its first moments.